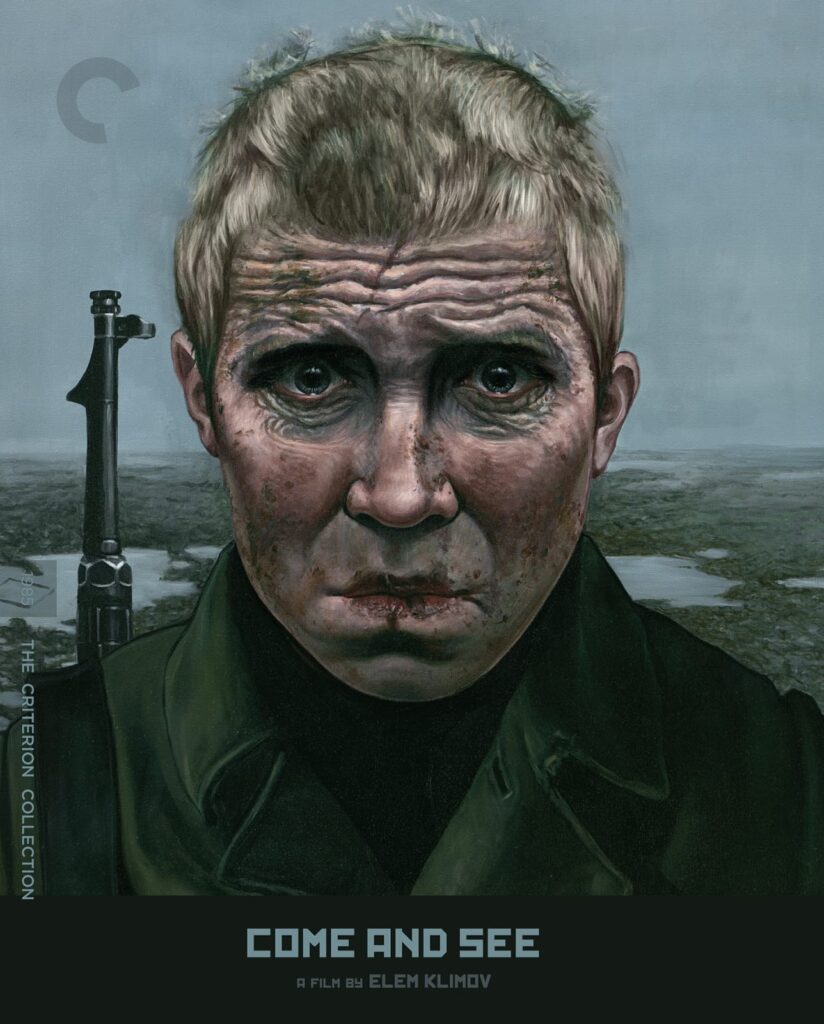

For one of my classes during the previous semester, I had the opportunity (well, more of an obligation that thankfully ended up being a pleasure) to watch a classic film called Come and See, directed by Elem Klimov. It’s a very raw and visceral piece showcasing the gritty horrors faced by Byelorussians at the hand of the Nazis during their invasion of the USSR in WWII. Klimov does not leave anything to the imagination, as we see countless examples of the atrocities committed by the invading Nazis, from mass murders, burnings, rapes, and tortures. We see these through the eyes of our protagonist named Flyora, a teenage boy who volunteers for the Soviet resistance forces. One of the more interesting things about this film is how we see Flyora change throughout the story. In the beginning, we see this youthful optimism in his face, with him not thinking too much about the ramifications of joining the military despite his mother’s tearful pleading, laughing and joking around. However, we, as well as Flyora, quickly see the grand and somewhat rose-tinted notion of war turned on its head. As the film continues, we see Flyora witness more and more disgusting acts committed by the Nazis, from surviving a gruesome bombing[1], finding his village elder burned alive[2], seeing his comrades killed by bullets and explosions, witnessing mass executions and more. Throughout all these events, we notice Flyora’s face become progressively wrinkled and haggard, giving him the look of a very aged and depressed man by the end of the movie. The changes are amplified by the consistent central zooming on his face, perfectly showcasing his emotional reactions to the harrowing events he has witnessed. Klimov uses this perspective to paint a wonderfully horrifying picture of war that makes you feel firsthand what the victims of these Nazi atrocities in Byelorussia faced decades ago. This overarching theme of war stripping away one’s innocence is peppered throughout with other characters as well when they experience Germany’s brutality.

This movie’s message coupled with the period it covers makes for an interesting dichotomy. WWII, and warfare in general, was seen as a grand calling during Stalin’s era as seen in many posters and works in the era. It was used as a positive way to enforce a sort of union among the people in the USSR, similar to the usage of liberation in the early days of the revolution. This film presents us with that idealized view of warfare early on with Flyora’s unwavering determination to fight despite numerous objections from others, only for it to end with him broken and detached, with regret and pain filling him throughout this experience. I also found it interesting in connection to the end of this film, where Flyora shoots at a picture of Hitler constantly through flashbacks of the war and then stops when the image of baby Adolph appears.[3] I feel like this represents how warfare can turn innocent children, such as Flyora into desensitized and harrowed men, a far cry from the romanization and usage of warfare as a tool during the Stalin era. The usage of Mozart’s Requiem is also apt in this scene, as a Requiem is a mass for the dead used in Catholicism, symbolizing even further how war leads to death not only physically, but also death within oneself. Flyora joins his fellow soldiers in the end as they march onwards, signifying the unending nature of war and perhaps even the lasting effect of its horrors, as we can’t escape them and can only hope to move forward.

[1] Klimov, Come and See, (1985), 0:35:00–0:36:00

[2] Ibid, 0:56:30–0:58:00

[3] Ibid, 2:09:25–2:12:50